Wales has a long history of fishing. In South Wales this is clearer than anywhere else. Tenby was among the earliest and most noteworthy Welsh fishing ports in the 18th century. By the 19th century, Milford Haven, Swansea, and Cardiff were emerging as the largest trawling ports in Wales, with Milford becoming the sixth largest port in the UK by 1906. At the other end of the spectrum, one cannot forget the small, but famous cockle fisheries of Penclawdd, Ferryside, and Laugharne or the coracle fishermen of the River Teifi.

However, in the present day, fishing heritage occupies a conflicted position in society, politics, and the economy. Beyond the marketing of Welsh cockles, mussels, laverbread and coracle-caught salmon and sewin, heritage is seldom used to promote the seafood caught by the small-scale inshore fishery. This refers to the fleet of boats under 10m in length that fish within 9 miles of the shoreline, and accounts for approximately 90% of the Welsh fishing fleet. This industry is in a precarious position. The Welsh fishing fleet is particularly vulnerable to being de-prioritised and marginalised: post-Brexit, media outlets and the government have repeatedly represented the fishing industry’s contribution to the UK economy as ‘only 0.1%’, and the Welsh fleet is smaller than those in England and Scotland in terms of size and GDP. While the industry is kept alive by the perseverance of fishermen and grass-root organisations such as the Welsh Fishermen’s Association, it remains an unforgiving livelihood with inadequate support from the government.

On the other hand, fishing heritage, in terms of romantic visions of former fishing communities, has the potential to entice visitors. Beginning in the 18th and 19th centuries, fisherfolk and their material and intangible attributes became subjects of fascination under the gaze of urban visitors from England and Wales. Today, tourism makes a greater contribution to the Welsh economy than any other country in the UK. This is most pronounced along the coastline where communities have been significantly transformed in recent decades through outmigration, holidaymaking, and gentrification.

On the surface, fishing heritage is alleged to provide many opportunities to deindustrialised coastal towns. Boosting the tourism and leisure industries, creating employment, instilling pride in local communities, and inspiring young people are among the benefits cited by proponents of fishing heritage. However, exercising caution and criticality are central to the approach that I am exercising to fishing heritage. Whether the impact of heritage is positive or negative greatly depends on the agents that control, and ideologies that underpin, the heritagisation process. It stems from this, and the above considerations, that my PhD research will ask how fishing heritage has mediated the reconfiguration of fishing communities in South Wales.

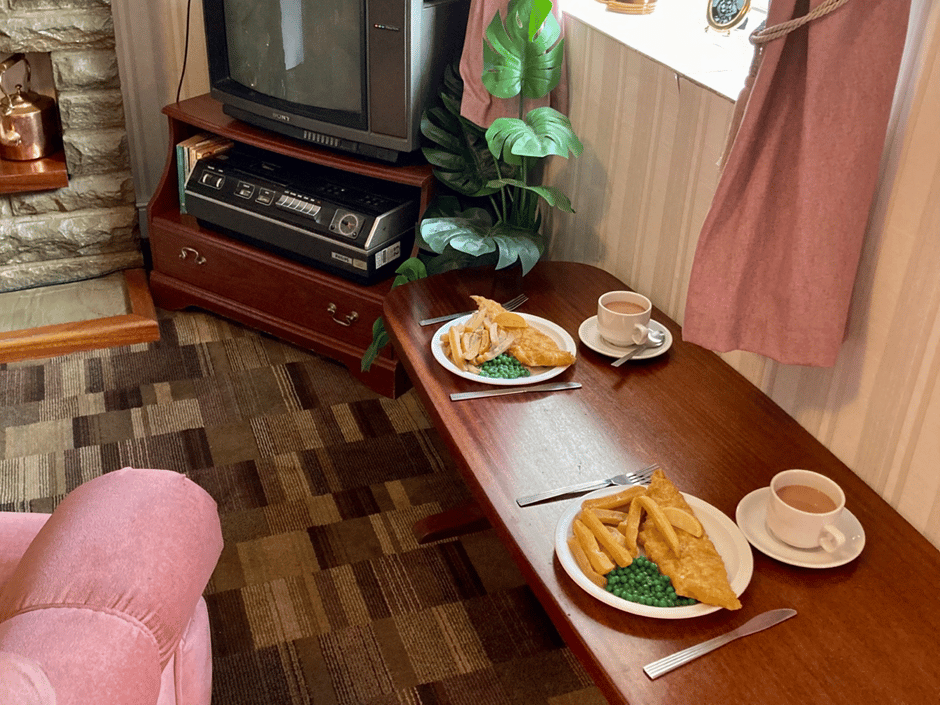

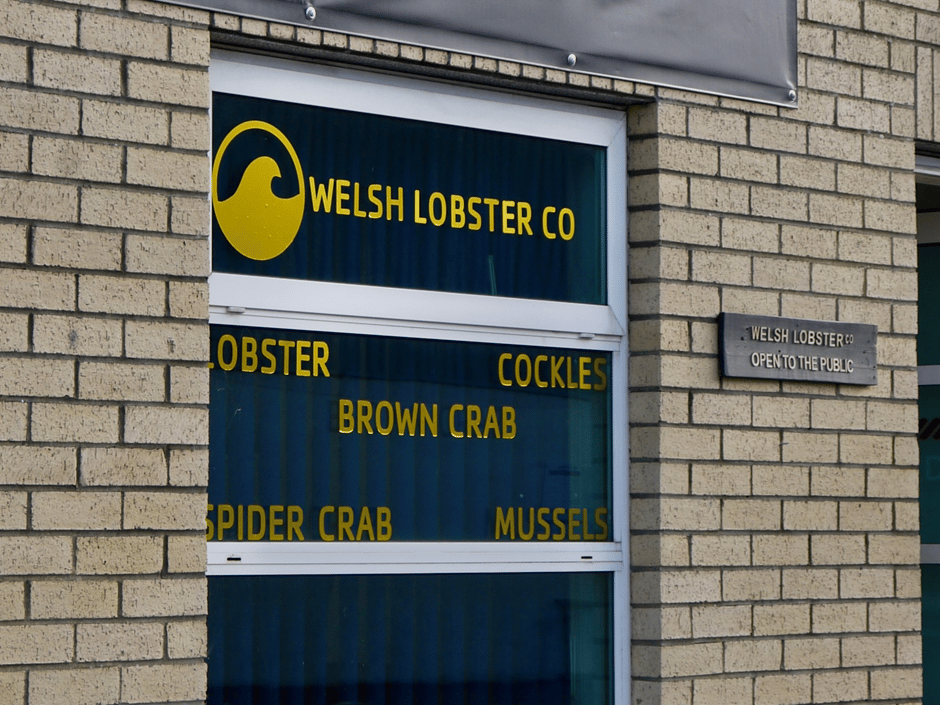

A second challenge and contradiction that I will address is that of the export and import of fish. A clear asset of the Welsh fishing industry is its capacity to appeal to the values of small-scale and artisanal production. Yet this largely goes unnoticed by the local populous. On average, 80% of the fish and shellfish caught by the Welsh fleet is exported to the likes of Spain, France, and Portugal. This includes crab, lobster, whelk, and scallop, as well as smaller volumes of sea bass, sole, monkfish, skate and ray. By contrast, as a nation, over 80% of the fish we consume is imported from elsewhere in Europe and Asia. The most popular species include cod, tuna, salmon, and prawns. My project will respond to this imbalance by deconstructing consumer tastes in seafood from the 19th century up until the present day and exploring whether a redefined fishing heritage could contribute to the localisation of seafood consumption.

Importantly, the aim here is not to promote the consumption of certain fish or shellfish species because there is a historical precedent or in order to preserve a ‘given’ intangible heritage. This is typically the route followed by culinary tourism and the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List. I believe this would be problematic for two primary reasons.

Firstly, it reproduces trends of heritagisation that tend to alienate local communities and promote gentrification. In the same way that former working landscapes become sterilised and aestheticized to become holiday destinations that entice tourists, traditional foods can be transformed into luxury high-dining experiences with over-inflated prices.

Secondly, stipulating that we should consume specific seafood types is ineffectual and even counterproductive. The primary species caught by the local fleet are highly variable. In 2021, the highest value species caught in Wales were whelk, lobster, scallop, and crab. 30 years ago, the highest value species caught were plaice, spurdog and skates and ray. Fishermen will pursue species that are most profitable, depending on demand and market pressures. However, variation in fish stocks is also a factor, and one that is not necessarily within human control. We need to operate greater adaptability and flexibility in our tastes. This is the opposite of the trend set in motion by industrial food production where our tastes have been standardized to optimise efficiency and profit for global agribusiness, multinational supermarkets, and fast-food chains.

My adopted approach is to explore fishing heritage in ‘alternative, less anthropocentric and more ecologically adapt terms’ (Olsen and Pétursdóttir 2016). To contemplate whether, and if so how, heritage could be drawn upon to support small-scale fishing as a viable enterprise and encourage a move towards localising food production. Fishing heritage will be explored not as a given, static and transhistorical quality that resides in coastal communities, but as a historically specific, constructed category that pervades all aspects of the industry, from catch, to sale, to consumption. The emergence of heritage will be understood as pertaining to social, economic, and political factors, as well as the histories of fish populations and marine ecosystem health that have shaped what species are caught and the trajectory of coastal communities.

Promoting an industry that has been in decline for decades, and encouraging consumption of seafood, let alone locally-sourced shellfish, are not small tasks and may even seem superfluous at a time when 4.2 million people in the UK are living in food poverty. However, we are on the brink of ecological collapse. The need to consider radically different habits of extraction, production and consumption is becoming more imminent. Therefore, while as a first point my PhD research will contribute to wider calls for small-scale production and localising food production, my hope is that this will touch upon how we may re-structure our value systems and break the capitalist cycle.

Katherine Watson is a first-year PhD student in history and contemporary archaeology.

Email: 2216575@swansea.ac.uk

Twitter: @KatherineWats0n

This research is generously funded by DePOT (Deindustrialization and the Politics of our Time) and Swansea University.